It has already been established on this blog that I am messy by default. My desk, room, garage, workshop, and van were in a constant state of disorder. I have gone to great lengths to improve that, but without medicine and constant vigilance, I would resort back to my natural state.

However, I am neat when it counts. When I leave a customer site, I leave it better than when I arrived. I learned that in the Marine Corps: when we stopped in the field for a while, we always removed evidence that we had been there before we left. When we setup in a non-tactical area of operations, we would clean up litter that was there before us. In Iraq, the Marines make sure that they leave a town with more water, schools, and soccer balls than when they arrived.

I have a strong work ethic. I get it from my father. He taught me that a job worth doing is worth doing right. That has a lot of depth to it. There is existentialism written all over it. Would you and should you do a job that isn't worth doing? Why would you do a job that isn't worth doing? What makes it worth doing? And if it is worth doing, why would you not do it right? What is the point of having a job that is truly worth doing and then doing it wrong or only doing half the job?

I exist to work. I do not exist to earn a paycheck, or to make an employer rich, or to call myself by a title. I exist to do something. That something is defined by me and it transcends "jobs", employers, salaries, and titles. At the end of my life, no one will care what server I saved or which router I installed. If anyone cares at all, they will care how I did more than what I did. That includes how I treated people, whether I conformed to the big picture or not, and what effect my existence had on the my sphere of influence. Did I leave the world better off than when I found it or did I leave a mess for someone else to clean up?

In August of 1997, I had been out of the Marines for a year and was still trying to find myself. I was working for a Pepsi distributor at the time, which was a low paying job with no benefits but the best job I could find at the time. I traveled to grocery stores to fill their shelves and build displays.

I was the most junior guy on my team, which meant that for a long time I did not have my own regular stores; I filled in where I was needed. On August 13th, my boss called and offered me my own route. The guy who had the route was getting fired for performance issues. Getting my own stores was a proud moment for me. Mainly, it meant that you could always go to these stores to see how well I did my job.

The first store on my route was the Price Chopper in Stanley, KS. I arrived at 6am on August 14th, 1997 as proud as could be. As soon as I walked into the backroom, I was greeted by the manager of the backroom. He was an old man whose life did not turn out the way he had dreamed and he took it out on everyone around him. He chewed my ass for the condition of his store. I explained that the person responsible had been terminated and that I was the polar opposite. I agreed that his store was atrocious, and that it required my top priority.

I should have delivered by speech to the brick wall; this guy just wanted to be an a-hole. I will never forget how angry he made me by assuming I was another slacker. I considered telling my boss. I considered telling his boss. I considered breaking his fingers. I considered ripping his tiny little heart out of his chest and stomping on it. I was a little angry.

His biggest complaint was the pile of damaged Pepsi packages. We were supposed to repackage as much as we could and then make a safe and secure pallet of the unrecoverables to ship out. It was dirty work: the breakers were often covered with sticky spray from a punctured can, as well as the grime that accumulates quickly in a backroom.

Taking care of damage was also time consuming. You had to locate new packaging and box tape, then clean the product, then build a package one can at a time, etc... It could turn a ten hour day into a twelve hour day. It could also make you late getting to your next store, which would result in another ass-chewing by that manager who was angry about life, his two ex-wives, his daughter's tattoo, and the lack of Pepsi on his shelves.

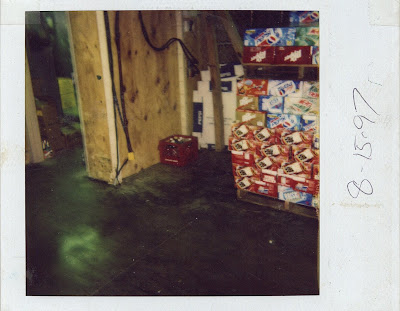

The damage at Stanley Price Chopper had built up for a long time. The backroom manager was sick of it, and he was not going to give me a fair chance to correct the problem. He pulled out a Polaroid camera and took a picture of the pile to show my boss:

I love a challenge, and this guy had thrown down the gauntlet. I knew that I wouldn't be in trouble for this mess; it wasn't mine and my boss knew it. I knew it was a low-priority for my boss; my higher priorities were filling shelves and building displays for several stores. I also knew this backroom guy barely mattered: he did not make purchasing decisions and he would give himself a coronary any day. However, this was a chance to rise above average, to prove to myself and anyone else watching that I had something more inside of me than a $10 per hour manual labor job. I had a chance to make myself proud, and maybe someone else along the way.

On 8/14/97, I worked hard. I left the Stanley Price Chopper with full shelves of product (all facing forward), well constructed and attractive displays, and full vending machines-but the backroom still looked like a disaster. I had five more stores to worry about.

I arrived at other stores that had suffered similar neglect, but I was not met with the same ferocity that greeted me in Stanley. It was long day of heavy lifting, working my way down crowded aisles of oblivious shoppers, driving down crowded roads of oblivious drivers, and plenty of tedious labor. After I finished my route, I returned to Stanley. By now, I was all alone back there and could work in peace. I cleaned up the mess, made my rows of Pepsi neat, and left the store exactly the way I should as a conscientious and proud merchandiser. Then I went looking for a Polaroid.

I asked the young girl at the front counter about the camera, and she found it easily. I think I told her I needed a picture of a product display or something, but I doubt she really cared. I took two pictures of the scene below:

The backroom manager had pinned the photo of the Pepsi mess next to his desk to remind himself the next time my boss came by. I stole it; I am not proud of stealing, I believe it is always wrong, and I do not endorse situational ethics. Even though the backroom manager was wrong for holding me accountable for the damage, I was wrong for stealing the photo. I am sorry. In any case, I did it. I replaced his messy photo with a photo of the clean spot.

Nothing ever came of this. I never had a run-in with the backroom manager again; I think I avoided him for the sake of sanity and to not have to answer for the stolen photo. I wish I could have been there when he reached for the replaced photo. Was he bewildered? Did he expect me to do this? Did he care at all, or did he just shrug, mentally check Pepsi off his hit list, and move on to the Milk guy? Did the Coke guy suffer more because of me?

It is over ten years later, and I still remember the incident, I still have the photos. On 8-14-97 I wanted to kill a man. The Marine Corps was still fresh in my psyche then: the pride, the training, the instincts. I was really angry at the time. I was able to keep my wits and suppress my angriest reactions, but it wouldn't have taken much for me to snap and splatter that old crotchety never-has-been.

On 9-27-07, I want to thank that man. Shame on me for my anger and thoughts of how to extend his suffering. He did me a great favor; he brought out the best in me. I would have done a good job in Stanley's Price Chopper over time, and that damage pile would have shrunk slowly, but surely, over several weeks if he had left me alone. By attacking me, he forced me to find a way to do my job better.

Moreover, he gave me solid evidence of things inside of me that many people do not have in such quantity: a great work ethic, personal pride, capacity for work, and high standards. I already knew I had those things; I had proved them before. My Marine Corps service was a certificate in such things. However, this was one more bullet point to help me know who I really was: a proud man who goes above and beyond, who gets "it" done, and who holds himself to a higher standard than those around him.

I keep these photos to remind myself of the kind of work I do. I get tired. I get discouraged. I get my feelings hurt by employers and customers. I get sick of the crap that employees get dumped on them over time. There are times when I feel like a bad employee, or I feel like I am incapable for doing anything right. These photos remind me what I am feeling is a temporary reaction to a temporary situation. The static reality is that I am a great employee who makes the impossible happen and I exceed expectations any time I want to.

Thank you, grumpy old man. You made me better that day. You have made me better every day since with the photo you took. When I remember you, I work harder and do it better. I can only hope that I have that effect on someone else with my life too.

And I want to thank my dad even more. I have had many lessons in work ethics, but without solid fundamentals I never would have gotten "it". My dad did three great things in raising me that have made me a great employee: First, he made me work. I am used to hard work, I have a greater capacity for work, and I expect to work hard because my dad made me work while other kids were playing or sleeping. Second, he made me do the job right; he corrected me when it was wrong and showed me how to fix it. By setting the bar high and teaching me that, "A job worth doing is worth doing right," my dad gave me an advantage over the people around me.

Third, and most important, my dad worked hard himslef. He did well and got promoted at work. He worked hard at home on maintenance and improvement. He worked hard in the community on various projects such as the Jaycees and the zoning board. He worked hard on me, even when I was a hopeless lost-cause. That example makes the difference. Words are one thing, but actions make a lesson stick.

1 comment:

Larry,

I am Priscilla Smith. Terri Lowry's daughter.

This post was encouraginG!

Thank you, I look forward to reading more.

Post a Comment